It has been three years since the microprocessor industry first had to deal with the existence of the Specter attack. Over time, many variants of Spectre have emerged, mitigated by existing patches or new fixes.

But now, a team from the University of Virginia School of Engineering has discovered “a line of attack that breaks all Spectre defenses, meaning that billions of computers and other devices across the globe are just as vulnerable today as they were when Spectre was first announced.”

According to the report, Spectre can attack CPUs of the AMD Ryzen and Intel Core series via a side-channel by taking advantage of the CPU’s micro-op caches.

The researchers have named the new approach for a side-channel attack, with the help of which actually protected data can be extracted from a processor, with the name — I See Dead µops: Leaking Secrets via Intel/AMD Micro-Op Caches.

In addition to the current desktop processors up to the latest generations of the AMD Ryzen 5000 and Intel Core i-11000 (test) series, all CPUs in the HEDT and server sector have been affected since 2011.

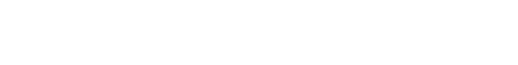

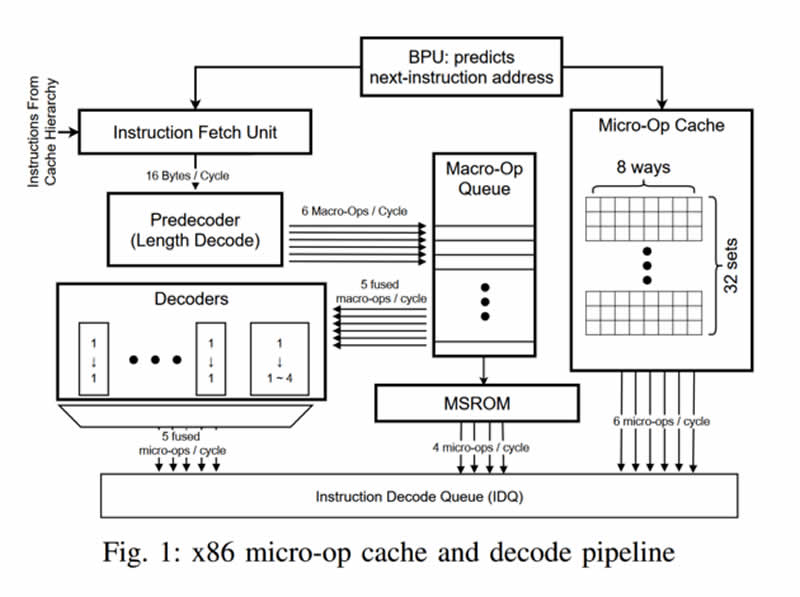

Unlike previous Spectre attacks, which primarily took advantage of the main memory or shared L3 caches as well as speculative execution via branch prediction, the new side-channel attack goes one level deeper and directly attacks the so-called micro-op caches, a very fast SRAM in the immediate vicinity of the CPU cores. In a proof of concept, the team led by Ashish Venkat was able to overcome the isolation of the most diverse memory address areas with the method.

In another report, the research team compares the side-channel attack with a hypothetical scenario at an airport.

“Think about a hypothetical airport security scenario where TSA lets you in without checking your boarding pass because (1) it is fast and efficient, and (2) you will be checked for your boarding pass at the gate anyway.

A computer processor does something similar. It predicts that the check will pass and could let instructions into the pipeline. Ultimately, if the prediction is incorrect, it will throw those instructions out of the pipeline, but this might be too late because those instructions could leave side-effects while waiting in the pipeline that an attacker could later exploit to infer secrets such as a password.”

Since all the current defenses developed for Spectre protect the processor at a later stage of speculative execution, they are useless in the face of new attacks.

The implementation of appropriate patches against this type of attack, for example, via Intel’s Software Guard Extensions (SGX), would cost a lot of performance since the iTLB (Instruction Translation Lookaside Buffer) would have to be emptied beforehand, the researchers continue.

“In the case of the previous Spectre attacks, developers have come up with a relatively easy way to prevent any sort of attack without a major performance penalty. The difference with this attack is you take a much greater performance penalty than those previous attacks.

Patches that disable the micro-op cache or halt speculative execution on legacy hardware would effectively roll back critical performance innovations in most modern Intel and AMD processors, and this just isn’t feasible.”

The universities of Virginia and California, which were involved in the investigation, notified AMD and Intel of the vulnerability in mid-April. Intel says the current countermeasures for Spectre and previous variants are sufficient to repel the three new attacks discovered by researchers at the University of Virginia.